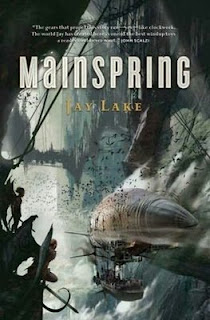

Mainspring by Jay Lake

Although Jay Lake's Mainspring takes place in an alternate history of Edwardian earth, the moment of the "break" which Karen Hellekson notes is necessary for alternate history to be different from ours, happens much earlier. Unlike other alternate histories which might suppose a break in a verifiable historical event, Lake's fictional conceit in Mainspring is far more cosmic, occurring at the moment of creation. The entire planet of Mainspring is bisected by a massive wall, separating it into the industrialized Northern hemisphere, and the bucolic, pre-industrial Southern hemisphere.

Although Jay Lake's Mainspring takes place in an alternate history of Edwardian earth, the moment of the "break" which Karen Hellekson notes is necessary for alternate history to be different from ours, happens much earlier. Unlike other alternate histories which might suppose a break in a verifiable historical event, Lake's fictional conceit in Mainspring is far more cosmic, occurring at the moment of creation. The entire planet of Mainspring is bisected by a massive wall, separating it into the industrialized Northern hemisphere, and the bucolic, pre-industrial Southern hemisphere.The hero of the tale is Hethor Jacques, a clock maker's apprentice who receives a visit from a suitably steampunk angel Gabriel, "bright as any brasswork automaton" (11). Hethor is entrusted with a quest to find the legendary "Key Perilous," one of seven sacred artifacts given to humanity by the Brass Christ following his "horofixion" on a "wheel-and-gear" instead of cross (12). Hethor's journey ultimately takes him from his comfortable, predictable life in New Haven, Connecticut, to the court of the viceroy of Boston, before bording an airship in the Royal Navy which is headed towards the Equatorial Wall. Hethor is told by Gabriel at the outset of his quest that the Key Perilous lies in the Southern Earth, and so it is of course, where he finally finds himself.

The book is as divided as the world it describes. The action in the Northern Earth has a sort of standard "hero's journey" feel to it, and Lake does an admirable job of making this early twentieth century United States strange enough to feel otherworldly, while maintaining the verisimilitude of period necessary for successful historical (even alternate historical) fiction to work. However, while the action of the first half keeps feeling as though it should be more enjoyable, I personally never found that it did. Or perhaps it's more what reviewer Lord Brandoch Daha observed, that each segment is good, but lacks overall cohesion:

On the downside, his novel Mainspring works out to be a bit less worthy than the sum of its parts. Each chapter is good. Each stage of the adventure is interesting, even exciting. Lake's alternate Earth is an intriguing place. His protagonist, a 16 year old boy named Hethor, sets out on a quest, follows it through while touring the world, and succeeds all is well. But as a whole, the parts don't quite fit together.The second half is so different from the first in setting and pacing that it feels like one is reading an entirely different book. And whereas in the first half, the reader is suspicious that Hethor is getting bailed out of every perilous situation by a higher power, in the second, the reader is convinced. While many books beg you to skip to the end to see how it comes out, by the middle of Mainspring, I was pretty sure I knew already.

I blame Hethor Jacques.

Lake's lead character is one of the most bland and unappealing characters I have read in some time. His lack of appeal is not due to any vice or ugliness, but to the entire absence thereof. Sadly, Hethor is lacking as much in any real virtue as he is vice, lacking beauty as much as ugliness. He is the epitome of the flat character, given just enough nuance to seem lifelike, but in many ways as clockwork and predictable as the universe he inhabits. Things seem to happen around Hethor, not to him. He initiates nothing, and hardly even reacts to that which is initiated upon him.

Despite having no real sense of agency, Hethor does ultimately complete his quest. This would be a spoiler, but for the fact that a spoiler implies suspense, that one may be in question of whether or not the hero will succeed. But in Lake's Mainspring, by the time Hethor has reached the Southern Earth, the reader is no longer questioning whether or not Hethor will find the Key Perilous and reset the earth's mainspring, but only how. The when is clear - a few pages before the end of the book.

The idea of the deus ex machina is an authorial taboo which Lake uses as the premise of Mainspring. If the God of a clockwork universe sent you on a mission, you're going to complete that mission. You have been effectively wound up on a divine scale, and sent to do your job. Other people can die along the way, and many do--but you will not. You will complete your quest. You can fall off the miles-high Equatorial wall, but God's "angels" will catch you. This in itself is a fascinating idea, and the way in which Lake ties the idea of clockwork into Hethor's ability to hear the machinery of the earth coming off its track develops into the equally interesting idea that one who can hear the clockwork will ultimately understand the clockwork, and be able to assert their will upon it, i.e., perform magic. Hethor becomes a sort of cybernaut in real space, like characters from cyberpunk who can manipulate virtual reality. Hethor asserts his will upon the clockwork universe, at one point producing a field of grass and flowers in the midst of an arctic waste. This is a cool idea, but it makes for terrible story telling.

Story needs crisis. And Mainspring never really gets into crisis mode.

Sure, we're told the world is winding down and will soon end, but the sense of apocalyptic doom is missing. While it is a bit cliché, it would have helped heighten a sense of tension if the world falling apart might have actually had an effect on Hethor's adventures. He witnesses the earthquakes and tidal waves from the safety of an airship, which reduces the level of threat.

Further, Hethor never really gets into crisis. He gets beat up, wounded, and nearly killed on several occasions, but he's pulled out of the frying pan and/or fire before the reader can really begin to worry about him. We know he has to make it to the end of his quest, and by the end of the book, we're not really even all that worried when he dies. We're pretty sure, given the thematic content of the book, that he'll be resurrected shortly. After all, he is doing the same work the Brass Christ did centuries earlier.

There may be a deeper, ironic idea here, related to the "god-in-the-box" approach of religious fiction where God makes all things right at the very end, but if there is, I missed it entirely. I applaud Lake for carrying his conceit through to its logical conclusion, by not pulling the rug out from under the reader with a "man behind the curtain" in the place of God. A cursory reading of period fiction from the era steampunk emulates and plays within reveals that while God might have been dead, people were still talking about him, or at the very least still playing by his rules. However, there is a way to have a higher power involved in the working out of the main action in a way which leaves the reader in suspense. Tolkien did it. Lewis did. Stephen King has pulled it off in books like The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon and Desperation.

Sadly, it isn't done here. And while I love the universe Lake has created for his characters to live in, I can't say the same of those characters, or of the action they embody in Mainspring. I have hope though, given the glimmers of hope I had in the first half, and the buzz that Mainspring's sequel, Escapement, has gotten Lake's world back on track.

I must give a final kudo to Lake for effectively steampunking Christianity. It's no mean feat to give a major world religion a retro-futurist overhaul. In this respect, Lake is successful, as evidenced not only by the myth of the Brass Christ and the Horofix, but by the inclusion of what I can only describe as a steampunked version of the Lord's Prayer:

“Our Father, who art in Heaven

“Craftsman be thy name

“Thy Kingdom come

“Thy plan be done

“On Earth as it is in Heaven

“Forgive us this day our errors

“As we forgive those who err against us

“Lead us not into imperfection

“And deliver us from chaos

“For thine is the power, and the precision

“For ever and ever, amen. (102-03)

NOTE: I have heard the word "clockpunk" bandied about as a descriptor of Mainspring. A new subgenre of a subgenre is not needed here. If we allow Verne and Wells as the grandfathers of steampunk, then clockwork has always been part of what steampunk has been. Consider Phileas Fogg, who lives his life with clockwork precision (thanks Howard Hendrix!), or the nature of Wells' time machine. Clockwork is steampunk. No need for another term, people.

Comments

Post a Comment