The League of Heroes by Xavier Mauméjean

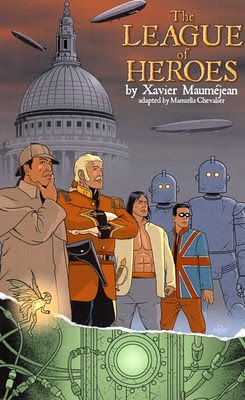

Last year, I was contacted by a steampunk enthusiast from France who recommended a number of French steampunk works to me. The only one in English translation was Xavier Mauméjean's La Ligue des héros, or The League of Heroes as translator Manuella Chevalier renders it. With no context for Mauméjean's reputation as a writer (is he taken seriously? has he won awards?), I was uncertain of what to expect from Heroes. The cover by French comic artist Patrick Dumas didn't help any, wonderful as it is, showing Sherlock Holmes, protagonist Lord Kraven, Tarzan, and English Bob (who is clearly an homage to Captain America's Bucky), standing in a line, ready to save the world. Those familiar with European comic styles through Heavy Metal or other avenues might appreciate Dumas' spartan line art, but most North Americans might dismiss the cover as amateurish, or wonder if the book is a graphic novel. The jacket text sheds further light, but only on the certain sections of the book.

Divided into four distinct parts, it is difficult to talk about what The League of Heroes is about without delivering spoilers. In the hope of intriguing readers, I will deliver information about the first two parts, since they deliver a good deal of what Mauméjean contributes to the steampunk aesthetic. About the second two, I will only say that I'm very glad I had no idea about where the book would go, as it made for an exceedingly enjoyable read. I'm highly recommending this one.

Part One reads like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen if Alan Moore had faith in the human race and a sense of humor. It follows the incredibly preposterous adventures of The League of Heroes, formed the grossly obese Phileas Fogg to protect the Empire of Albion. The heroes and villains arrayed against each other is a who's who of pulp adventure: the aforementioned heroes, along with Kid Colt, the Steel Comrade, Auguste de Grandin, Baron Stromboli, and Captain Hook, versus Peter Pan (in a wonderful reversal of rolls), the Jade Mask, Doctor Fatal, and Prince Sinbad (who stands in for Nemo as the mysterious submarine terrorist).

Stylistically, the first part vascilates between deftly sketched vignettes of the League's adventures and excerpts from the daily news, press releases, and political speeches. Like Pynchon, Mauméjean's prose spans events in a few lines that take other writers pages. It is, in many ways, what Jonathan Green's Unnatural History should have been, striking the proper mix of deadpan delivery on the surface, with ironic tone beneath. Lord Kraven's opening killshot sets this tone immediately:

Part Two opens with a drastic shift in content and tone: from the fantastic world of the League to the pedestrian existence of a man the reader knows only as George, who has recently had his "unremarkable house, in an unremarkable suburb" invaded by his wife's estranged and amnesia-stricken father. One suspects immediately that this man might be Lord Kraven. But as he begins regaining his "memory" by reading comic books as history, the reader begins to wonder if he isn't just delusional. I won't spoil the surprise of which is the truth, despite the presence of a really great quotation on page 251 that says a great deal about some people's perception of steampunk.

Instead, I'll talk about recursive fantasy, which The League of Heroes is a wonderful example of. In the Encyclopedia of Fantasy (EF) by Clute and Grant, recursive fantasy is described as "exploit[ing] existing fnatasy settings or characters as its subject matter." Recursive fantasy can be parody, pastiche, or revisionist re-examinations of earlier works such as fairy tales, pulp adventures, or extraordinary voyages. After reading The League of Heroes, it almost seems as though Mauméjean read this entry, and then wrote the book. Not only does League fulfill all of those requirements, being both tribute and indictment of simple comic-book heroism, the text also plays with what the EF calls "the flavor of true [recursive fantasy]", whereby "'real' protagonists [encounter intersecting] worlds and characters which are as 'fictional' to them as to us" (805). It is this intersection between the "real" and the "fictional" that sets The League of Heroes apart from other steampunk works. Pynchon plays with these ideas in Against the Day, but League presents them in a more accessible fashion. Mauméjean's prose is less dense than Pynchon's.

Steampunk often engages in the first aspect of recursive fantasy, utilizing existing fictional characters from nineteenth century adventure tales: Jeter's Morlock Night; Kim Newman's Anno Dracula; Mark Frost's The List of Seven, and The Six Messiahs; Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neil with the mother-of-all-recursive fantasies, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. And while it is deeply satisfying to see old characters reworked to suit new sensibilities and styles, I found it deeply satisfying to be forced by Mauméjean's text, to wrestle through both the fantasy of the Empire of Albion, as well as the mundane reality of 1960s England, wondering how it all fits together. I found the ending perfectly appropriate, but others might be disappointed. I'll be interested to see what the readers here at Steampunk Scholar think about it. I highly recommend it for those who love the world Moore and O'Neill introduced us to, but are looking for something a little less cynical, and a little more complex.

Divided into four distinct parts, it is difficult to talk about what The League of Heroes is about without delivering spoilers. In the hope of intriguing readers, I will deliver information about the first two parts, since they deliver a good deal of what Mauméjean contributes to the steampunk aesthetic. About the second two, I will only say that I'm very glad I had no idea about where the book would go, as it made for an exceedingly enjoyable read. I'm highly recommending this one.

Part One reads like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen if Alan Moore had faith in the human race and a sense of humor. It follows the incredibly preposterous adventures of The League of Heroes, formed the grossly obese Phileas Fogg to protect the Empire of Albion. The heroes and villains arrayed against each other is a who's who of pulp adventure: the aforementioned heroes, along with Kid Colt, the Steel Comrade, Auguste de Grandin, Baron Stromboli, and Captain Hook, versus Peter Pan (in a wonderful reversal of rolls), the Jade Mask, Doctor Fatal, and Prince Sinbad (who stands in for Nemo as the mysterious submarine terrorist).

Stylistically, the first part vascilates between deftly sketched vignettes of the League's adventures and excerpts from the daily news, press releases, and political speeches. Like Pynchon, Mauméjean's prose spans events in a few lines that take other writers pages. It is, in many ways, what Jonathan Green's Unnatural History should have been, striking the proper mix of deadpan delivery on the surface, with ironic tone beneath. Lord Kraven's opening killshot sets this tone immediately:

"Half a moustache suited Lord Kraven perfectly. It had, nevertheless, been a close-shave--Prince Spada's blade having nearly run him through the throat.This was one of my Christmas holiday reads, and the rollicking pace of the first part kept a smile on my face as Kraven and his companions effortlessly engaged in hyperbolic exploits: "Lord Greystoke had just returned from a difficult mission in which he had made contact with a giant gorilla on an island near Sumatra. His body was covered in bandages" (17). But while the book maintains a gleefully ironic tone, it isn't meant to be taken lightly. Before long, the heroes begin to question the ease with which they always win, but must also continue the battle. Unlike Green, Mauméjean's heroes are more self-aware, and wonder at the simplicity of their steampunk world:

The foremost hero of Albion fixed his tie, looked at himself in the mirror one last time and proceeded to shoot his attacker in the head. The bullet...continued through the wall, ricocheted against the Tower's metal frame and went on to kill Ambrosio Terracota, the Prince's henchman, splattering his brains across the floor." (9)

"Yes, of course, I always forget that we are the good guys," he said with irony. "Always ready to defeat a new threat, to foil a new convoluted plot, to stop a new would-be world conqueror. But it all sounds very hollow right now. Consider our foes...They always tell us their plans in great details after they capture us, they always make a last minute mistake which enables us to escape and defeat them... Yes, we win, but only until the next time, for they always return..." (65)Like Boilerplate, the League makes commentary on past social injustices, such as Bloody Friday in May of 1919 (which takes place in May of 1916 in the League's alternate history), the event catalyzing English Bob's departure from the League of Heroes. Finally, the only one left is Lord Kraven, and when he initiates a more global iteration of the League, is killed in an airship explosion.

Part Two opens with a drastic shift in content and tone: from the fantastic world of the League to the pedestrian existence of a man the reader knows only as George, who has recently had his "unremarkable house, in an unremarkable suburb" invaded by his wife's estranged and amnesia-stricken father. One suspects immediately that this man might be Lord Kraven. But as he begins regaining his "memory" by reading comic books as history, the reader begins to wonder if he isn't just delusional. I won't spoil the surprise of which is the truth, despite the presence of a really great quotation on page 251 that says a great deal about some people's perception of steampunk.

Instead, I'll talk about recursive fantasy, which The League of Heroes is a wonderful example of. In the Encyclopedia of Fantasy (EF) by Clute and Grant, recursive fantasy is described as "exploit[ing] existing fnatasy settings or characters as its subject matter." Recursive fantasy can be parody, pastiche, or revisionist re-examinations of earlier works such as fairy tales, pulp adventures, or extraordinary voyages. After reading The League of Heroes, it almost seems as though Mauméjean read this entry, and then wrote the book. Not only does League fulfill all of those requirements, being both tribute and indictment of simple comic-book heroism, the text also plays with what the EF calls "the flavor of true [recursive fantasy]", whereby "'real' protagonists [encounter intersecting] worlds and characters which are as 'fictional' to them as to us" (805). It is this intersection between the "real" and the "fictional" that sets The League of Heroes apart from other steampunk works. Pynchon plays with these ideas in Against the Day, but League presents them in a more accessible fashion. Mauméjean's prose is less dense than Pynchon's.

Steampunk often engages in the first aspect of recursive fantasy, utilizing existing fictional characters from nineteenth century adventure tales: Jeter's Morlock Night; Kim Newman's Anno Dracula; Mark Frost's The List of Seven, and The Six Messiahs; Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neil with the mother-of-all-recursive fantasies, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. And while it is deeply satisfying to see old characters reworked to suit new sensibilities and styles, I found it deeply satisfying to be forced by Mauméjean's text, to wrestle through both the fantasy of the Empire of Albion, as well as the mundane reality of 1960s England, wondering how it all fits together. I found the ending perfectly appropriate, but others might be disappointed. I'll be interested to see what the readers here at Steampunk Scholar think about it. I highly recommend it for those who love the world Moore and O'Neill introduced us to, but are looking for something a little less cynical, and a little more complex.

Hi

ReplyDeleteI'm a french reader in fond of Steampunk litterature. For me, "The league" is the worst exemple of steampunk french books you can find.

I think Xavier Maumejean has been published just beacause the story happen in London. But we have many other kinds of writers in France who deserve to be famous.

Nevertheless, french people are waiting for some books never translated. For instance, we are always waiting for Morlock's Night, and Leviathan.

Lord Orkan Von Deck

Good to have a French perspective Lord Von Deck! I was given the recommendation to read Maumejean by another French fan of steampunk, so I guess this may be one of those "love/hate" books. Don't be too excited for Morlock Night in translation - it's not all that great - Leviathan on the other hand is pure brilliance.

ReplyDelete