Larklight by Philip Reeve

I'm fond of quoting D.H. Lawrence's statement that we should "trust the art and not the artist" to my students early in the semester when I teach introduction to Literature. As you can see from the slide I've posted below, I conflate Lawrence's famous quotation with Philip Pullman's The Golden Compass. I tell the students how Pullman denied being an author of fantasy in an interview with Powells.com. I then explain that the polar bear in the image has opposable thumbs, is wearing special armor it forged for itself, and can talk. I also point out the golden compass itself in the heroine Lyra's hand as a divination device. I note the absence of Lyra's daemon, Pantalaimon, and lament the absence of my daemon, and wonder at it not being in class with me. I remark on the absence of their daemons. "Clearly, we are not dealing with reality," I conclude, "but some level of fantasy. It would seem I cannot trust Mr. Pullman to tell me what sort of book he has written."

I espouse a lite version of Roland Barthes' "Death of the Author" approach: I do not think understanding a text necessarily requires knowledge of the author, or what they thought of their text. This lecture usually precedes our discussion of Flannery O'Connor's "A Good Man is Hard to Find." O'Connor herself saw the short story, in which an entire family is killed by an escaped convict and his thugs, as a tale of redemption and grace. Most students find that reading ludicrous, and I tend to agree with them. Short of being possessed by the Holy Spirit in the final moments of the tale, the Grandmother O'Connor ostensibly crafts as the messenger of redemption is incapable of the sort of epiphany the author suggests she has. As Stephen Bandy has stated, "to describe the Grandmother as the vessel of divine grace, almost in spite of herself, is to transform her into a creature who simply has nothing to do with the Grandmother's character, as given."

I currently feel the same sort of distrust for Philip Reeve, who posted last month that he thinks steampunk "stinks" and vainly attempts to gain some creative distance from steampunk for his Mortal Engines books. It's not quite as blunt a move as Pullman saying he didn't write fantasy, but it's close: methinks thou dost protest too much, Mr. Reeve (especially when he tries distancing himself further in this post where he imagines lino and herringbone stamped metal on the lower decks of his traction-city-London. It's like reading a post by someone who was "steampunk before it was cool" but is redecorating their house now that it's popular). Since Reeve has long since removed the post from his blog, I'm posting a section of it here courtesy of Wis[s]e Words, who has a great post on Reeve's dismissal of steampunk:

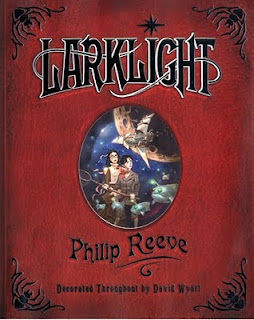

While he might be able to dodge the steampunk label for Mortal Engines, Reeve himself admits that his Larklight books "fall squarely into this category." We wouldn't need the artist to tell us this, because the art speaks for itself (go to the Larklight website to get a glimpse of how much of an understatement this is). And when I say art, I of course mean text, but in the case of Larklight, I also mean David Wyatt's fantastic illustrations throughout the text.

This is a book you can judge by its cover, and from the artwork on the inside of the cover. Opening up into a two-page spread, the reader is treated to an array of Victorian-style advertisements for "Pure Icthyomorph Liver Oil," "White Star Aether Cruises," and the "Rain & Co. Mk II Auto-Butler (The 'Crichton' Model!)" to name just a few. While I listened to Larklight on audiobook (an experience I can't recommend: I was unimpressed by the choice of an adult reader for a child narrator, given that Full Cast Audio could find a David Kelly for Kenneth Oppel's books), I always made sure to leaf through my hardback copy (which is on sale in Canada at Indigo/Chapters for only $5.99 - the website says sold out, but use the "tell us your location" function for copies at your local store), so as to enjoy all the wonderful illustrations. The full title on the title page reveals more steampunk feel: Larklight, or The Revenge of the White Spiders! or To Saturn's Rings and Back! A Rousing Tale of Dauntless Pluck in the Farthest Reaches of Space, as Chronicled by Art Mumby, with the aid of Mr. Philip Reeve and decorated throughout by Mr. David Wyatt. Reeve uses the "found manuscript" approach favored by a number of nineteenth century fantastic writers such as Edgar Allen Poe in MS Found in a Bottle. These sorts of nods to earlier writers and influences are likely what resulted in Reeve writing Larklight and Mortal Engines without any knowledge of steampunk as a growing "movement," as he calls it.

Coming back to my idea of "Roland Barthes" lite, I disagree with Barthes to an extent, as I think it's important to understand influence and context of a written work - I also believe we can learn more about a text by researching the author, but I'm dubious about it as a first approach. I think that if a story is unintelligible without annotation by the author, it's not much of a story. Knowing, as Reeve admits, that he was "inspired by the Science Fiction of HG Wells and Jules Verne" only corroborates what a reader would likely suspect while reading Larklight. Readers familiar with Jeff Wayne's prog-rock concept album of War of the Worlds might smile when introduced to Richard Burton's Martian wife Ulla, which could easily be a nod to the "Oo-lah" sound the Martians made. At the very least, finding out that "Richard Burton, the great British explorer and secret agent" has been given the title 'Warlord of Mars' should cause fans of Edgar Rice Burroughs to chuckle a little. The book is filled with these little tributes to Reeve's inspirations.

Reeve continues his homage to the style of nineteenth century writing through chapter headers such as "In Which We Find Ourselves Imprisoned on the Plain of Jars and Contemplate a Ghastly Fate (Again)." One gets an excellent sense of the whimsical, witty tone Reeve strikes for the voice of Art Mumby, who like the hero of Mortal Engines has a yearning for adventure. Unlike Tom, Art Mumby gets those adventures, without any strong negative epiphany whereby he is disabused of his romantic notions. Reeve focalizes the action of Larklight through Art with wonderfully whimsical results: like all young boys, he is annoyed by his older sister, who later provides diary entries to give her perspective once the two are separated. Reeve is equally adept with Myrtle's voice, since she is more entrenched in what passes for British colonialist sentiments in the Larklight universe. In this respect, Reeve is equally as successful with Larklight as he was with Mortal Engines at imbedding Bigger Ideas inside a tightly woven adventure tale. While the book can obviously be read for pure entertainment value, there are brief references to racial othering that could be explored by an ambitious teacher or parent.

The spaceships of Larklight are reminscent of Dungeons and Dragons Spelljammer roleplaying game, or the ships of Disney's Treasure Planet: they are masted vessels capable of flying through the aether of outer space. Here Reeve utilizes technofantasy to its best advantage, in the "chemical wedding" that occurs in an aether ship's "alchemical engine room," or "wedding chamber":

What was most unexpected, but of great interest to me, was the way in which Reeve treats the Shapers of the Larklight universe. I don't want to say too much about the Shapers, as it would create a spoiler of one of the best reveals in the book, but I was struck by how much the Shapers echoed C.S. Lewis' angelic eldila and Oyéresu in The Space Trilogy, which in turn owe some debt to J.R.R. Tolkien's Eldar and Valar in The Silmarillion. The Oyéresu are a science-fiction version of angels, while the Valar are mythologized versions of angels, or lesser gods. Both serve a higher power, and in Tolkien's case, assist in the act of Creation.

This is a link one can easily establish through Google. In an interview, Reeve openly admits C.S. Lewis' The Magician's Nephew as a favorite childhood read. Given his blog post about steampunk, no one seems to have ever bothered to ask him if he saw steampunk as an influence. It appears as though an analogous chain of inspirations that resulted in Pearl Jam and Stone Temple Pilots producing similar sounds in the '90s may have produced works from Reeve (who claims to have had the ideas for Larklight and Mortal Engines in the '80s, when steampunk was in its infancy) that have similarities to Blaylock and Moorcock. The result of those similar or shared influences coalesced into what we now call steampunk.

I don't necessarily disagree with the criticisms Reeve levels against steampunk. There are many examples to support his invective. However, there are numerous instances that contradict his criticisms, and his own novels are among them. Ironically, Reeve states the following in a post-script:

What might have been a smarter move on Reeve's part would have been to admit his participation in steampunk, and continue to seek to elevate this supposed "genre cul-de-sac." He can go ahead and put a sword in Fever Crumb's hand, but I've seen the website, and it screams steampunk. The same goes for the Larklight and Mortal Engines books. Steampunk might stink, but it's a stink Philip Reeve has already contributed to.

Thanks to regular Steampunk Scholar reader Harmsden for bringing Philip Reeve's post to my attention, as it formed a nice frame for this post.

I espouse a lite version of Roland Barthes' "Death of the Author" approach: I do not think understanding a text necessarily requires knowledge of the author, or what they thought of their text. This lecture usually precedes our discussion of Flannery O'Connor's "A Good Man is Hard to Find." O'Connor herself saw the short story, in which an entire family is killed by an escaped convict and his thugs, as a tale of redemption and grace. Most students find that reading ludicrous, and I tend to agree with them. Short of being possessed by the Holy Spirit in the final moments of the tale, the Grandmother O'Connor ostensibly crafts as the messenger of redemption is incapable of the sort of epiphany the author suggests she has. As Stephen Bandy has stated, "to describe the Grandmother as the vessel of divine grace, almost in spite of herself, is to transform her into a creature who simply has nothing to do with the Grandmother's character, as given."

I currently feel the same sort of distrust for Philip Reeve, who posted last month that he thinks steampunk "stinks" and vainly attempts to gain some creative distance from steampunk for his Mortal Engines books. It's not quite as blunt a move as Pullman saying he didn't write fantasy, but it's close: methinks thou dost protest too much, Mr. Reeve (especially when he tries distancing himself further in this post where he imagines lino and herringbone stamped metal on the lower decks of his traction-city-London. It's like reading a post by someone who was "steampunk before it was cool" but is redecorating their house now that it's popular). Since Reeve has long since removed the post from his blog, I'm posting a section of it here courtesy of Wis[s]e Words, who has a great post on Reeve's dismissal of steampunk:

No, the problem that I have with Steampunk as a genre is that it’s basically dead. Returning again and again to the same tiny pool of imagery, the writers of Steampunk are doomed to endless repetition. What I used to love about Science Fiction as a teenager was the way that, when you picked up one of those yellow Gollancz SF titles at the library, you had no idea where it would take you; it might be to some dazzling technological future or post-apocalyptic wasteland; it might be to another planet; or it might all be set in the present, just around the corner. But when you pick up a Steampunk book you know pretty much exactly where you’re going; it will take place in an ‘alternate’ nineteenth century which will be neither as complex nor as interesting as the actual nineteenth century. There will be airships; rich villains will be hatching plots involving clockwork and oppressing the workers; rich heroes will see the error of their ways. Most of the characters will not display any of the attitudes or beliefs of the past, but will act and speak like modern people in Victorian fancy dress.

[…]

Steampunk is a genre cul-de-sac: it’s Science Fiction for people who know nothing about science; historical romance for readers whose knowledge of history comes from costume dramas.

While he might be able to dodge the steampunk label for Mortal Engines, Reeve himself admits that his Larklight books "fall squarely into this category." We wouldn't need the artist to tell us this, because the art speaks for itself (go to the Larklight website to get a glimpse of how much of an understatement this is). And when I say art, I of course mean text, but in the case of Larklight, I also mean David Wyatt's fantastic illustrations throughout the text.

This is a book you can judge by its cover, and from the artwork on the inside of the cover. Opening up into a two-page spread, the reader is treated to an array of Victorian-style advertisements for "Pure Icthyomorph Liver Oil," "White Star Aether Cruises," and the "Rain & Co. Mk II Auto-Butler (The 'Crichton' Model!)" to name just a few. While I listened to Larklight on audiobook (an experience I can't recommend: I was unimpressed by the choice of an adult reader for a child narrator, given that Full Cast Audio could find a David Kelly for Kenneth Oppel's books), I always made sure to leaf through my hardback copy (which is on sale in Canada at Indigo/Chapters for only $5.99 - the website says sold out, but use the "tell us your location" function for copies at your local store), so as to enjoy all the wonderful illustrations. The full title on the title page reveals more steampunk feel: Larklight, or The Revenge of the White Spiders! or To Saturn's Rings and Back! A Rousing Tale of Dauntless Pluck in the Farthest Reaches of Space, as Chronicled by Art Mumby, with the aid of Mr. Philip Reeve and decorated throughout by Mr. David Wyatt. Reeve uses the "found manuscript" approach favored by a number of nineteenth century fantastic writers such as Edgar Allen Poe in MS Found in a Bottle. These sorts of nods to earlier writers and influences are likely what resulted in Reeve writing Larklight and Mortal Engines without any knowledge of steampunk as a growing "movement," as he calls it.

Coming back to my idea of "Roland Barthes" lite, I disagree with Barthes to an extent, as I think it's important to understand influence and context of a written work - I also believe we can learn more about a text by researching the author, but I'm dubious about it as a first approach. I think that if a story is unintelligible without annotation by the author, it's not much of a story. Knowing, as Reeve admits, that he was "inspired by the Science Fiction of HG Wells and Jules Verne" only corroborates what a reader would likely suspect while reading Larklight. Readers familiar with Jeff Wayne's prog-rock concept album of War of the Worlds might smile when introduced to Richard Burton's Martian wife Ulla, which could easily be a nod to the "Oo-lah" sound the Martians made. At the very least, finding out that "Richard Burton, the great British explorer and secret agent" has been given the title 'Warlord of Mars' should cause fans of Edgar Rice Burroughs to chuckle a little. The book is filled with these little tributes to Reeve's inspirations.

Reeve continues his homage to the style of nineteenth century writing through chapter headers such as "In Which We Find Ourselves Imprisoned on the Plain of Jars and Contemplate a Ghastly Fate (Again)." One gets an excellent sense of the whimsical, witty tone Reeve strikes for the voice of Art Mumby, who like the hero of Mortal Engines has a yearning for adventure. Unlike Tom, Art Mumby gets those adventures, without any strong negative epiphany whereby he is disabused of his romantic notions. Reeve focalizes the action of Larklight through Art with wonderfully whimsical results: like all young boys, he is annoyed by his older sister, who later provides diary entries to give her perspective once the two are separated. Reeve is equally adept with Myrtle's voice, since she is more entrenched in what passes for British colonialist sentiments in the Larklight universe. In this respect, Reeve is equally as successful with Larklight as he was with Mortal Engines at imbedding Bigger Ideas inside a tightly woven adventure tale. While the book can obviously be read for pure entertainment value, there are brief references to racial othering that could be explored by an ambitious teacher or parent.

The spaceships of Larklight are reminscent of Dungeons and Dragons Spelljammer roleplaying game, or the ships of Disney's Treasure Planet: they are masted vessels capable of flying through the aether of outer space. Here Reeve utilizes technofantasy to its best advantage, in the "chemical wedding" that occurs in an aether ship's "alchemical engine room," or "wedding chamber":

Pipes, tubes and ducts snaked all around me, tangling over the walls and roof in a way which reminded me dimly of Larklight's boiler room. In the heart of it all squatted the great alembic: the vessel in which the secret substances which power our aether-ships are brought together and conjoin in the chemical wedding. (78)Here is one of the instances when Reeve imbeds a Bigger Idea in what appears to be only a reveal of the aether ships' impulsion. Art remembers that the Royal College of Alchemists refuse to operate the wedding chamber for pirates, but while aboard Jack Havock's pirate-ship the Sophronia, Art witnesses the chemical wedding being performed by a female alien, without the assistance of the "great racks of books and tables of logarithims" the Royal College of Alchemists require (80-81). While the alien-as-racial-other is a somewhat tired concept in certain circles, one must remember that it would likely be a new concept for many of Larklight's target audience. Again, a teacher or parent could easily open a discussion with students or children about ideas of expectation, stereotyping, and ignorance out of a passage such as this.

What was most unexpected, but of great interest to me, was the way in which Reeve treats the Shapers of the Larklight universe. I don't want to say too much about the Shapers, as it would create a spoiler of one of the best reveals in the book, but I was struck by how much the Shapers echoed C.S. Lewis' angelic eldila and Oyéresu in The Space Trilogy, which in turn owe some debt to J.R.R. Tolkien's Eldar and Valar in The Silmarillion. The Oyéresu are a science-fiction version of angels, while the Valar are mythologized versions of angels, or lesser gods. Both serve a higher power, and in Tolkien's case, assist in the act of Creation.

"He had met the creatures called the eldila, and specially that great eldil who is the ruler of Mars, or in their speech, the Oyarsa of Malacandra. The eldila are very different from any planetary creatures. Their physical organism, if organism it can be called, is quite unlike either the human or the Martian. They do not eat, breed, breathe, or suffer natural death, and to that extent resemble minerals more than they resemble anything we should recognise as an animal. Though they appear on planets and may even appear to our senses to be sometimes resident in them, the precise spatial location of an eldil at any moment presents great problems. They themselves regard space as their true habitat, and the planets are not to them closed worlds but merely moving points - perhaps even interruptions - in what we know as the solar system and they as the Field of Arbol." (Lewis, Perelandra, 1-2)

"Who made the Universe and lit the suns? Who shaped the Shapers? For Shapers are not gods, just servants of that invisible, universal will which set the stars in motion...when a Shaper vessel has done its work, it dies, and the Shaper on board it dies too. At least, they choose to cease to be--we are not alive in the same way you are, so we can never really die." (Reeve 326)I'll be interested to do further study on the relationship here, but want to withhold drawing strong conclusions at this point, because I haven't read the rest of the Larklight books, and I need to re-read The Space Trilogy with these thoughts in mind. At the very least, it was an interesting moment for me, given that James Blaylock has cited C.S. Lewis as a major influence on his work. I wouldn't go suggesting that Lewis stands as a precedent to steampunk, but his Space Trilogy certainly seems to be a limited inspiration for these two instances. From one vantage, this isn't terribly surprising, as Lewis was clearly writing in the modes of nineteenth century science-fantasies involving space travel, rather than the science-fiction of his contemporaries writing for John W. Campbell Jr.'s Astounding Science Fiction or Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories. Steampunk is based on the fantastic literature of the industrial and pre-war eras, as opposed to the science fiction of the depression years and beyond.

This is a link one can easily establish through Google. In an interview, Reeve openly admits C.S. Lewis' The Magician's Nephew as a favorite childhood read. Given his blog post about steampunk, no one seems to have ever bothered to ask him if he saw steampunk as an influence. It appears as though an analogous chain of inspirations that resulted in Pearl Jam and Stone Temple Pilots producing similar sounds in the '90s may have produced works from Reeve (who claims to have had the ideas for Larklight and Mortal Engines in the '80s, when steampunk was in its infancy) that have similarities to Blaylock and Moorcock. The result of those similar or shared influences coalesced into what we now call steampunk.

I don't necessarily disagree with the criticisms Reeve levels against steampunk. There are many examples to support his invective. However, there are numerous instances that contradict his criticisms, and his own novels are among them. Ironically, Reeve states the following in a post-script:

The final blow to the alternate-world version of Mortal Engines fell when Philip Pullman's Northern Lights was published, itself set in an alternate world with various Steampunky elements. But the world of Northern Lights has a whole parallel physics and cosmology too, which I think lifts it safely clear of the Steampunk ghetto.One protesting Phil invokes another protesting Phil as an appeal to create distance from the milieu they've been labeled as writing in: Michael Chabon's busy trying to defend quality genre fiction, while the Phils and William Gibson are busy denying their roots in fantasy, steampunk, or cyberpunk (to be clear, invoking the term genre fiction isn't an admission of steampunk as genre - I still hold it's an aesthetic that is most often applied to forms popularly labeled genre fiction). I can't deny Reeve the right to rail against steampunk. He's free to think what he wants of the steampunk aesthetic. It just smacks of the same bad taste I get in my mouth whenever Harrison Ford talks shit about Star Wars, as though he weren't a set carpenter when Lucas asked him to play Han Solo.

What might have been a smarter move on Reeve's part would have been to admit his participation in steampunk, and continue to seek to elevate this supposed "genre cul-de-sac." He can go ahead and put a sword in Fever Crumb's hand, but I've seen the website, and it screams steampunk. The same goes for the Larklight and Mortal Engines books. Steampunk might stink, but it's a stink Philip Reeve has already contributed to.

Thanks to regular Steampunk Scholar reader Harmsden for bringing Philip Reeve's post to my attention, as it formed a nice frame for this post.

Thanks for the namecheck! I must come clean however and say that it was JNL over at Steampunk Empire who first drew my attention to Reeve's post.

ReplyDeleteKudos on bringing 'Death of the Author' into it. I always think of it whenever I hear writers like Margaret Atwood complaining that their work has nothing whatsoever to do with SF or fantasy. Fear of ghettoes creates ghettoes.

Indeed - Atwood's a great candidate for such study. The last time I studied Atwood's works, the lecturer treated us to nearly 40 minutes of biography. I could really care less. I think the work needs to stand on its own before you go rooting through the biographical information. Borges said that all writing is ultimately biographical, but that doesn't mean an author is best suited to saying "what their work is, or is about." We all have our blindspots - authors are no different. Lewis claims Narnia is a Christian allegory, and it can certainly be read as such, but I've read some convincing papers that demonstrate how Lewis undermines the Christian content with the amount of pagan imagery he utilizes. Not saying I agree with that 100%, but it shows how the author isn't always right, even about their own work.

ReplyDeleteWhatever we may think of Reeve trying to distance himself after the fact, I'm gratified that someone else is noticing the repetitions.

ReplyDeletePlus, I may have to run down to Chapters and track down Larklight. There's about 30 copies spread around town ^_^

I'm very much in agreement with his critiques, but I've heard them from other writers as well, but none of those saw fit to distance themselves from something they were clearly contributing to. Jess Nevins, Jeff Vandermeer, Jim Blaylock, Gail Carriger, and J Daniel Sawyer have all made comments to the effect they're not thrilled with where steampunk is/was at, but are committed to adding something to elevate it, not abandon it.

ReplyDeleteYes, you of all folks ought to own a copy of Larklight. You'll get a lot of those sideways references throughout.

Thanks for linking my name with that of Philip Pullman. I wish I had his sales figures.

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure which website you've seen. The Larklight one does indeed scream steampunk, which is right and proper since I've never pretended that Larklight is anything but steampunk of the steamiest and punkiest sort.

mortalengines.co.uk and scholastic.com/fevercrumb were set up by my publisher: I have no say in their design.

I wish you had his sales figures too! I was referencing the Mortal Engines site: http://www.mortalengines.co.uk/

ReplyDeleteI should be clear that in conflating steampunk with Mortal Engines, I am only doing this insofar as steampunk's aesthetic qualities. I am in no way comparing Mortal Engines with The Affinity Bridge and saying, "These are the same!" My approach is to view steampunk an aesthetic tool box - so I would say that Mortal Engines is a post-apocalyptic adventure story that utilizes the steampunk aesthetic, among other things. If I were to view steampunk as a fixed genre, I wouldn't classify Mortal Engines as steampunk either: but I find the "Victorian SF" definition of steampunk to be too limiting and not inclusive of the texts, art, and fashion which have been identified with steampunk culture.