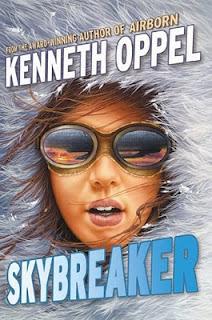

Skybreaker by Kenneth Oppel

In her somewhat overstated (and likely very tongue-in-cheek) post "The Fallacies of Steampunk as a Genre," Alexandra Victoria Hollingshead gives would-be steampunk writers some advice, including the proscription, "Airship may only be used once if the story does not take place on an airship at any point." I laughed when I saw this, because it seems more a reaction to the fan-culture of steampunk than the literature. In the 30+ novels I've read now, plus a few comics and short stories, I can't think of one where airships were superfluous affectations. It's one of the lessons I learned participating in the Great Steampunk Debate: there's a world of difference between steampunk on paper and steampunk on the street. I want to say more about this in an upcoming post, but for now I'll limit my comments to saying that in email correspondence with Polish cartoon writer Krzysztof Janicz and I have been discussing how steampunk is often (mistakenly, I would say) conflated with people who "are" steampunks, which causes people to equate the guys in goggles, politicos with pocket-watches, and lolitas in lace with the fiction. This is why I continue to approach my study from an aesthetic perspective - once steampunk becomes an ideology, we're in Max Weber's backyard, and while that may prove an interesting study for someone, it won't be me.

In short, I'm not sure what fiction Hollingshead's blackballing of brown and censure of airships is reacting to, but it certainly wouldn't be Kenneth Oppel's Skybreaker, which, aside from Scott Westerfeld's Leviathan, is one of the best steampunk airship books currently available. I don't say this because Skybreaker is necessarily highly original or powerfully literary. Rather, it's the high level of derivation Oppel engages in that makes it so much fun. The book is pastiche and homage of Victorian Science Fiction, of the numerous Verne knock-off adventure films of the 1950s and '60s, written in the same spirit that Spielberg and Lucas were channeling when they made Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The continuing adventures of Matt Cruse and Kate DeVries begins with the discovery of the Hyperion, a ghost-airship, floating above 20,000 feet over the Indian Ocean. Matt is the only member of his oxygen-starved crew able to withstand the high altitude, and after rescuing them and their training vessel, becomes embroiled in a number of attempts to salvage the Hyperion, which is rumored to have vast treasure aboard. He is the only living person who knows the coordinates the Hyperion was last seen. When Cruse agrees to join the mysterious gypsy girl Nadira aboard the airship Sagarmatha, he is engaged in a race against other nefarious parties to reach the Hyperion first.

The book is great fun, with the same pacing Oppel used in Airborn. Of all the Matt Cruse books, Skybreaker is my favorite, since unlike Airborn which departs the setting of the airship, Skybreaker remains aloft for the majority of its adventure. I was impressed by Oppel's idea to use Tibetan Sherpas as the crew of the Sagarmatha, a skybreaker airship capable of flying at higher altitudes than regular airships. These Sherpas are so well-rendered, that when Matt and two of the Sherpas encounter an aerozoan, a species of sky-mollusk with electrifying tentacles, the reader is genuinely concerned for everyone's safety. These aerozoans are a wonderful monster, a threat that Oppel delights in repeatedly throwing at his cast of characters. Oppel never relents in his series of serial-like cliffhanger chapter endings, and the book rockets along, page after page-turning page.

Like I said in my post on Airborn, the mature reader knows Matt Cruse will survive. The older reader is less interested in whether Matt Cruse will survive than how he will. Further, Matt Cruse's survival isn't simply physical - it's spiritual, or shall we say, linked to his growing up. I hate using high-falutin' terms like bildungsroman for books like Skybreaker, not because I don't think the book deserves elevated terms, but because it somehow takes away from the way in which young adult adventure stories present coming-of-age tales. These aren't stories about how one really grows up, but they are rather hyperbolized versions of that. They are, to use Joss Whedon's term, "Life writ large." As in Sunnyvale, where Buffy Summers grows up with vampires and werewolves and demon principals, Matt Cruse is becoming a man, and Kate DeVries is becoming a woman while soaring far above the earth in airships, battling aerozoans and sky-pirates. Their teenage romance is thwarted by these physical dangers, as well as more real emotional challenges: jealousy, petty arguments, the intrusion of guardians, the considerations of class distinctions (which aren't all that unimportant even today). Their romance is far less bile-inducing than that of Meyer's Twilight, which can never really shed fully the fact that a one-hundred year-old bad boy is dating a teenage girl. For those who prefer less titillation in their teen romance, Matt and Kate's relationship is true to period - while the skybreaker airship might be considered anachronism, Matt and Kate's chaste courtship is not. Kate's chaperone is but one of the challenges the two youths face in falling in love.

But love isn't all that's on Matt Cruse's mind: he comes from a background of low means, and he sees the possibility of treasure aboard the Hyperion as a way to break free of the constrains of a life of near-poverty. Through the plot of Skybreaker, Matt undergoes a transformation of sorts, moving through the basic victim positions Margaret Atwood outlines early in Survival, her book on Canadian literature's preoccupation with obstacles and hostility resulting in the need to survive.

At the outset of Skybreaker, Matt attempts to deny his Victim position, trying to impress Kate by meeting her at the Jewels Verne, an expensive Paris restaurant (which is a wonderful joke, since only North Americans pronounce the French writer's name this way). He is repeatedly faced with his low-status, both in his inability to order anything more than a water while waiting for Kate to arrive, and in the waiter's contemptuous treatment of him. Matt moves from denial to Atwood's second victim position: "To acknowledge the fact that you are a victim, but explain it as an act of Fate, the Will of God...or Economics..." (37). Matt believes he will never truly be able to woo Kate unless he has money, since she is from a family of considerable means. Thus, he accepts he is a victim, but thinks this is the result of economics - if only he had the opportunities the rich do, he would have a better life. When he meets Hal Slater, captain of the Sagarmatha, he assumes Hal came by his wealth easily, only to later learn that Slater had to work hard and is still in peril of losing the Sagarmatha to the banks.

While Slater performs the role of competing suitor for Kate's attention, he also becomes a sort of accidental mentor to Matt, which ultimately leads to Matt moving to victim position three: "To acknowledge the fact that you are a victim but to refuse to accept the assumption that this role is inevitable" (37). Matt grudgingly sees his own possible future in Hal's reality of owning his own airship - Matt wants to someday become an airship captain, but wants to fast-track that through the treasure aboard the Hyperion. Atwood states that it is in this position is about "repudiating the Victim role," moving from anger towards oneself or fellow-victims to "energy channeled into constructive action" (38). This is when Matt is able to finally move to Position Four, "to be a creative non-victim."

Once Matt can get past being a victim of finances or social position, he is able to make the sacrificial decisions necessary to survive the traps and tribulations once the adventurers board the ghost-ship. While Oppel continually uses convenient coincidences to rescue his hero, the reader doesn't mind, because Cruse's most crucial tribulations are emotional, not physical. We thrill to the near-death episodes, but are most moved when Matt gets over his petty teenage proclivities. Some readers may find Cruse's propensity for jealousy frustrating, but I'd guess they'd be folks who hate revisiting what it felt like to be fifteen. For those who either are in the game of surviving adolescence, or for those who are looking for a trip of nostalgia, into a past that never was, or perhaps just down memory lane into their teenage years, Skybreaker is the ticket into a high-altitude take on "life writ large."

And it has more airships than you can shake a steampunk at, with every last one of them more than justified in the action. Watch for the escape from the airship hanger for a scene that just begs someone to film it.

Check out the Skybreaker website, including Kate DeVries's drawing of an Aerozoan - it's awesome!

Click here for a Skybreaker teacher's guide.

Steampunk as an ideology from a sociological perspective. To bad I'm not a writer. I would love to explore that.

ReplyDeleteMy thoughts on Weber started with a meditation concept of the Disenchantment of the World, and my revulsion to Josh Landy's thesis in 'The ReEnchantment of the World'. (For a short treatment of the book see the Entitled Opinions Podcast: http://french-italian.stanford.edu/opinions/landy_saler.html. Or you can take my word for it: "The world is disenchanted, the spiritual dimension has been exposed as a sham. That's ok, we always have the CSI chatroom (or StarTrek, or steampunk, or...) to numb that side of the brain.")

Beyond Landy, Weber is a portal into the worldview that makes steampunk/VSF/Scientific Romance so interesting to me. The triumph of Western Civilization, capitalism, rationalism. And yet he lived to see that magnificent edifice crumble in the Great War.

Jack, I don't know how else one would go about studying the lifestyle/ideology side of steampunk without resorting to sociology. Your comments here test those very waters. My M.A. thesis was very nearly about fan cultures as religious practice. The world is disenchanted, and I do think steampunk is one of the ways people are "numbing that side of the brain," or seeking to fulfill whatever part of the human experience religion serves. Many may take umbrage with that statement, since they're "spiritual," not religious, or will want to argue that the absence of God in steampunk is why they like it, but that's why I'm invoking Weber. You don't need a deity to be religious in Weber's approach to religion.

ReplyDelete