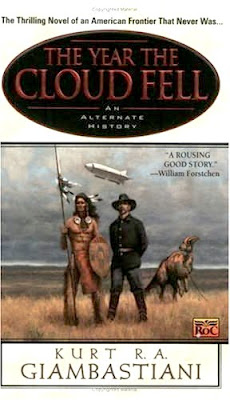

The Year the Cloud Fell by Kurt R.A. Giambastiani

It's Canuck Steampunk month, and here I am on the American Independence Day posting about an American writer's alternate history of the United States. I had no plan to post about The Year the Cloud Fell any time soon. It was in my "associated with steampunk" stack: books I've collected that come close to being steampunk, but likely aren't. In the wake of reading The Apparition Trail though, I needed something for contrast and comparison. How did another writer handle an alternate history where airships flew over the frontier? Further, while The Year the Cloud Fell is about the American frontier, the issue of First Nations in speculative fiction, especially alternate history, is a particularly Canadian issue.

I'll begin by recalling the attitude towards Native Americans and First Nations prior to the release of Dances With Wolves (I personally prefer the use of the term First Nations to refer to indigenous peoples in all of North America, though I am aware that some people in the U.S. still refer to these groups as Native Americans - I'm also aware that many First Nations people self-identify as Indians - as a Canadian, I'll be using the ostensibly Canadian term) . I grew up with comic books like The Apache Kid and The Rawhide Kid, when we still called indigenous North Americans Indians, when they were still "Redskins" and "Savages" in Westerns. Sure, there were overtures toward certain Indians (like Tonto) being "good guys," but most were bad guys. When you played Cowboys and Indians, the unspoken rules dictated that at least one of the Cowboys would be the Last Man Standing. I was very lucky to have my mother as a guiding force in this reading. She loves Westerns, but since she was a child, had wanted to, in her words, "be an Indian." She identified with First Nations people, and not in a New Age healing and meditation sort of way. There was no appropriation in my mother's love for First Nations people, unless you count the time she and my father went to one of those Wild West Photo Parlours and she wore the buckskin dress. As a result, the violent savages of Marvel's Wild West comics were tempered by my mother's love for First Nations culture. Dances with Wolves didn't seem like a huge step to me, but when I consider how it opened the way for a slough of positive films and books about historical First Nations heroes to be released into mainstream culture, I think it was a very good thing.

Yes, there was a certain consumer fetishism to it. With mainstream always comes junk. But the popularity of films like Dances With Wolves and The Last of the Mohicans paved the way for the release and/or re-release of books like Orson Scott Card's Alvin Maker series, specifically Red Prophet, Charles DeLint's Svaha, both of which are listed in Beyond Victoriana's "First Nation Sci-Fi & Technology Resources" as positive contributions to the perception of First Nations people in science fiction and fantasy. Kurt R.A. Giambastiani's The Year the Cloud Fell is also on that list, and I was pleased to see it there.

Before I return to the discussion of First Nations people, I want to make a brief digression into the difference between steampunk and nineteenth-century alternate history. It's interesting that both The Apparition Trail and The Year the Cloud Fell begin with their protagonists in the air, buffeted by storm weather. The difference between how the two handle it is crucial: in The Apparition Trail, the storm is supernatural, the method of flight is a perpetual motion air-bike, and the hero suffers air sickness, but lands safely; in The Year the Cloud Fell, the storm is natural, the method of flight is a prototype airship that does what real early airships do in a storm, and as a result the protagonist is wounded and taken into captivity.

I wouldn't qualify The Year the Cloud Fell as steampunk, because it tries too hard for verisimilitude. The flight of the air-bike in The Apparition Trail needs a perpetual motion machine, which in turn seems to need a different face of the moon to shine on the earth in order to work. The airship Abraham Lincoln in The Year the Cloud Fell works like a real airship does, and crashes much as real airships often did. Compared to the airships in Kenneth Oppel's Skybreaker, Chris Wooding's Retribution Falls, Michael Moorcock's Warlord of the Air, and Philip Reeve's Mortal Engines, Giambastiani's airship is an abysmal failure, flying for less than 20 pages of the novel's 336 before crashing. The airship serves as only one example of many, but serves to support my contention that steampunk is largely concerned with technofantasy, not anachronism. The airship of The Year the Cloud Fell is an anachronism in 1886: historically, it won't exist until 1906. But it will exist, whereas the airships of the other books will either never exist, or may yet exist: they are products of fantasy and future speculation, and as such aren't anachronisms. They belong in the fictional world created for them. The world of Kenneth Oppel's Skybreaker greatly resembles ours, but it still has fictional creatures populating its skies (as we'll see in the discussion of Oppel's books, the trilogy straddles alternate history and steampunk). Giambastiani doesn't need fictional fuels to fly his airship, because it's based in real-world physics. This is not an alternate history where the laws of nature have been changed (as in The Apparition Trail) or an alternate world where the laws of nature are different from ours. It is an alternate history, positing several crucial breaks in history.

One of the most significant breaks Giambastiani posits is that the dinosaurs didn't go extinct. Two species are included in The Year the Cloud Fell, which are called Whistlers and Walkers. The whistlers are a billed/beaked herbivore and are the primary means of transport for the Cheyenne Nation, while the Walkers are large predators, reminiscent of a T-Rex. I'm no paleontologist, so that's where my assessment of the dinosaurs ends, save to say that I applaud Giambastiani for avoiding cramming in a section explaining why they're there. It's ancillary to the action, and would only have bogged the proceedings down in unnecessary exposition.

Giambastiani utilizes a familiar plot line, a technique echoing the familiar history he subverts. Nearly everyone in North America has a sense of the part George Armstrong Custer played in American history, so using his son as the protagonist is the standard defamiliarization of the familiar speculative fiction so often produces. The plot line is Dances With Wolves, but only to a point. While some readers might judge him before reaching the end, they'd be foolish to do so. By the ending, I was convinced Giambastiani uses the familiar white-goes-native storyline to allow his ending to come as a surprise. He leads the reader right up to the door of the standard "final battle" trope of so much adventure fiction, and then subverts that as well, producing an ending that will satisfy almost all readers.

Like other writers I admire, Giambastiani carefully crafts his characters, so that we are not as interested in their battles as we are with whether or not they survive them. There is action, to be sure, but the focus is never gratuitously focused on the mechanics of combat. The Year the Cloud Fell is more concerned with the complexity of the ideas that lead to war, rather than war itself:

Many RaceFail posts and articles lack the subtlety of a conversation. They are textual analogues of a fight where one combatant has been tied up or hobbled. When the rules for the debate silence any side, it is not a debate, it is podium, a pedestal, a pulpit, and ultimately the content of such posts and articles become propaganda. If the champions of RaceFail are genuinely interested in seeing effective change, antagonism and assumption must be left behind. While it is a dangerous thing to do, we must always be open to conversation. It is not enough to say, "you ought to know." Ostensibly, the Colonialists should have known better, but didn't. When I look at the record of history to see which change agents were the most effective in the fight of racial equality, I think of Martin Luther King Jr., of Stephen Biko, of Nelson Mandela, and the current Dali Lama. These are all individuals who sought change, not through silencing their opposition, but in seeking to engage them in the conversation. To my RaceFail friends, I say this: don't ever get tired of explaining the basics. There are far too many people who don't understand where you're coming from, and they won't be swayed by being shown "the hand" and dismissed.

While I promised I wouldn't reveal the major spoiler, I'd like to present this moment between George Custer Jr. (One Who Flies) and Storm Arriving, a Cheyenne warrior as an exemplar of the conversation I'm espousing:

Giambastiani's book is a wonderful middle-path to journey along. While I read, I couldn't help but reflect upon Ay-leen the Peacemaker's Beyond Victoriana, one of my favourite blogs about speculative fiction and racial issues. Ay-leen's blog is a great example of what the conversation looks like. In her "First Nation Sci-Fi & Technology Resources" article, she demonstrates (without calling it this), a RaceWin list. Rather than targeting books that "fail," Ay-leen holds up the ones that win, and focuses on them. She encourages us to read them, and learn. She invites us into the conversation, and gives enough space for it to occur. Now go and do likewise.

Happy Independence Day to my American friends.

I'll begin by recalling the attitude towards Native Americans and First Nations prior to the release of Dances With Wolves (I personally prefer the use of the term First Nations to refer to indigenous peoples in all of North America, though I am aware that some people in the U.S. still refer to these groups as Native Americans - I'm also aware that many First Nations people self-identify as Indians - as a Canadian, I'll be using the ostensibly Canadian term) . I grew up with comic books like The Apache Kid and The Rawhide Kid, when we still called indigenous North Americans Indians, when they were still "Redskins" and "Savages" in Westerns. Sure, there were overtures toward certain Indians (like Tonto) being "good guys," but most were bad guys. When you played Cowboys and Indians, the unspoken rules dictated that at least one of the Cowboys would be the Last Man Standing. I was very lucky to have my mother as a guiding force in this reading. She loves Westerns, but since she was a child, had wanted to, in her words, "be an Indian." She identified with First Nations people, and not in a New Age healing and meditation sort of way. There was no appropriation in my mother's love for First Nations people, unless you count the time she and my father went to one of those Wild West Photo Parlours and she wore the buckskin dress. As a result, the violent savages of Marvel's Wild West comics were tempered by my mother's love for First Nations culture. Dances with Wolves didn't seem like a huge step to me, but when I consider how it opened the way for a slough of positive films and books about historical First Nations heroes to be released into mainstream culture, I think it was a very good thing.

Yes, there was a certain consumer fetishism to it. With mainstream always comes junk. But the popularity of films like Dances With Wolves and The Last of the Mohicans paved the way for the release and/or re-release of books like Orson Scott Card's Alvin Maker series, specifically Red Prophet, Charles DeLint's Svaha, both of which are listed in Beyond Victoriana's "First Nation Sci-Fi & Technology Resources" as positive contributions to the perception of First Nations people in science fiction and fantasy. Kurt R.A. Giambastiani's The Year the Cloud Fell is also on that list, and I was pleased to see it there.

Before I return to the discussion of First Nations people, I want to make a brief digression into the difference between steampunk and nineteenth-century alternate history. It's interesting that both The Apparition Trail and The Year the Cloud Fell begin with their protagonists in the air, buffeted by storm weather. The difference between how the two handle it is crucial: in The Apparition Trail, the storm is supernatural, the method of flight is a perpetual motion air-bike, and the hero suffers air sickness, but lands safely; in The Year the Cloud Fell, the storm is natural, the method of flight is a prototype airship that does what real early airships do in a storm, and as a result the protagonist is wounded and taken into captivity.

I wouldn't qualify The Year the Cloud Fell as steampunk, because it tries too hard for verisimilitude. The flight of the air-bike in The Apparition Trail needs a perpetual motion machine, which in turn seems to need a different face of the moon to shine on the earth in order to work. The airship Abraham Lincoln in The Year the Cloud Fell works like a real airship does, and crashes much as real airships often did. Compared to the airships in Kenneth Oppel's Skybreaker, Chris Wooding's Retribution Falls, Michael Moorcock's Warlord of the Air, and Philip Reeve's Mortal Engines, Giambastiani's airship is an abysmal failure, flying for less than 20 pages of the novel's 336 before crashing. The airship serves as only one example of many, but serves to support my contention that steampunk is largely concerned with technofantasy, not anachronism. The airship of The Year the Cloud Fell is an anachronism in 1886: historically, it won't exist until 1906. But it will exist, whereas the airships of the other books will either never exist, or may yet exist: they are products of fantasy and future speculation, and as such aren't anachronisms. They belong in the fictional world created for them. The world of Kenneth Oppel's Skybreaker greatly resembles ours, but it still has fictional creatures populating its skies (as we'll see in the discussion of Oppel's books, the trilogy straddles alternate history and steampunk). Giambastiani doesn't need fictional fuels to fly his airship, because it's based in real-world physics. This is not an alternate history where the laws of nature have been changed (as in The Apparition Trail) or an alternate world where the laws of nature are different from ours. It is an alternate history, positing several crucial breaks in history.

One of the most significant breaks Giambastiani posits is that the dinosaurs didn't go extinct. Two species are included in The Year the Cloud Fell, which are called Whistlers and Walkers. The whistlers are a billed/beaked herbivore and are the primary means of transport for the Cheyenne Nation, while the Walkers are large predators, reminiscent of a T-Rex. I'm no paleontologist, so that's where my assessment of the dinosaurs ends, save to say that I applaud Giambastiani for avoiding cramming in a section explaining why they're there. It's ancillary to the action, and would only have bogged the proceedings down in unnecessary exposition.

Giambastiani utilizes a familiar plot line, a technique echoing the familiar history he subverts. Nearly everyone in North America has a sense of the part George Armstrong Custer played in American history, so using his son as the protagonist is the standard defamiliarization of the familiar speculative fiction so often produces. The plot line is Dances With Wolves, but only to a point. While some readers might judge him before reaching the end, they'd be foolish to do so. By the ending, I was convinced Giambastiani uses the familiar white-goes-native storyline to allow his ending to come as a surprise. He leads the reader right up to the door of the standard "final battle" trope of so much adventure fiction, and then subverts that as well, producing an ending that will satisfy almost all readers.

Like other writers I admire, Giambastiani carefully crafts his characters, so that we are not as interested in their battles as we are with whether or not they survive them. There is action, to be sure, but the focus is never gratuitously focused on the mechanics of combat. The Year the Cloud Fell is more concerned with the complexity of the ideas that lead to war, rather than war itself:

"Only a short time ago he, too, had felt as they did, equating the Cheyenne's primitive existence with unabated savagery. But he had discovered instead a people with history, religion, government, and law. Their lives were violent at times and their technology was crude, but their ideas were not, and it was the ideas, he discovered. that defined a people.Giambastiani keeps that complexity in the forefront of The Year the Sky Fell, never allowing a simple solution to salve the reader's conscience of the relationship between First Nations and the rest of North America. This is not an escapist fantasy, a daydream where we can smile and "wish it were so," and feel a catharsis that fools us into thinking we've done away with the complex problems surrounding First Nations' issues. Instead, Giambastiani reminds us that such resolution is a conversation (I wish I could include a pivotal passage about this, but it's a major spoiler. I'll just cite the page number instead: 316). The Year the Cloud Fell challenges us all: those who recognize RaceFail and those of us who fail, alike. It's a challenge I'd like to echo.

Would we have been so proud, he wondered, had we lost our Revolution? Do we really judge ourselves not by the successes of our generals, but by the loftiness of our ideas?

No, he thought. We see only the vanquished and the victor. Ideas are a casuality of war and the commodity of historians." (248)

Many RaceFail posts and articles lack the subtlety of a conversation. They are textual analogues of a fight where one combatant has been tied up or hobbled. When the rules for the debate silence any side, it is not a debate, it is podium, a pedestal, a pulpit, and ultimately the content of such posts and articles become propaganda. If the champions of RaceFail are genuinely interested in seeing effective change, antagonism and assumption must be left behind. While it is a dangerous thing to do, we must always be open to conversation. It is not enough to say, "you ought to know." Ostensibly, the Colonialists should have known better, but didn't. When I look at the record of history to see which change agents were the most effective in the fight of racial equality, I think of Martin Luther King Jr., of Stephen Biko, of Nelson Mandela, and the current Dali Lama. These are all individuals who sought change, not through silencing their opposition, but in seeking to engage them in the conversation. To my RaceFail friends, I say this: don't ever get tired of explaining the basics. There are far too many people who don't understand where you're coming from, and they won't be swayed by being shown "the hand" and dismissed.

While I promised I wouldn't reveal the major spoiler, I'd like to present this moment between George Custer Jr. (One Who Flies) and Storm Arriving, a Cheyenne warrior as an exemplar of the conversation I'm espousing:

Storm Arriving smiled. "You have changed since I first met you."Conversation means slow change. Revolution brings fast, but ultimately false change. Change the ideas of a person, you have won. Change the rules about ideas, and you've only achieved suppression, which usually leads to further revolution, and no conversation. Giambiastini ends The Year the Cloud Fell with room for a sequel, but this has more to do with his tackling the complexity of his alternate history fairly than it does with simply looking to produce another book. For The Year the Cloud Fell to end other than it does is to seek a fairy-tale ending to a history we know wasn't 'happily-ever-after.'

"Have I?"

"Yes," he said. "You talk more like one of the People. I understand you much more now than I did before."

One Who Flies laughed. "The same is true for me," he said. "Now, when I hear you speak of the spirits of the earth or the sky, I feel as though I almost understand." He pointed to Storm Arriving's chest and the fresh scars left by the skin sacrifice. "I even think I might someday understand that. Someday."

"But not today," Storm Arriving said.

"No," George said with a sad smile. "Not today." (265)

Giambastiani's book is a wonderful middle-path to journey along. While I read, I couldn't help but reflect upon Ay-leen the Peacemaker's Beyond Victoriana, one of my favourite blogs about speculative fiction and racial issues. Ay-leen's blog is a great example of what the conversation looks like. In her "First Nation Sci-Fi & Technology Resources" article, she demonstrates (without calling it this), a RaceWin list. Rather than targeting books that "fail," Ay-leen holds up the ones that win, and focuses on them. She encourages us to read them, and learn. She invites us into the conversation, and gives enough space for it to occur. Now go and do likewise.

Happy Independence Day to my American friends.

Cowboys and dinosaurs...

ReplyDeleteNow that you've got your system down and are writing all these extra-brilliant reviews of things, I can sense a hit to my pocketbook...

An excellent assessment of a great book.

ReplyDeleteAnd thank you as well for the kind words about my blog. It's my intention for it serve as a resource and a jumping-off point for people when discussing complicated issues surrounding racial and cultural representation, something that's happening not only in steampunk but also in the greater sf/f community. I'm immensely happy to have your support. ^-^

~ Ay-leen