I'll be Holmes for Christmas, or Sherlock Holmes and the case of the missing holiday

For those interested, the new seasonal top bar contains images from Macy's Steampunk-themed holiday-window displays.

With tonight's release of Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows and the Christmas season upon us, I decided to kill two birds with one stone, by introducing my Sherlock Holmes series while simultaneously riding one of my scholarly hobby horses, the use or absence of Christmas/Christendom in steampunk.

Doing a series of Holmes posts was inspired by the release of the new Guy Ritchie film, as well as by Titan Books' line of Holmes' pastiches, both in the Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes series, marked by an asterisk below, and in the stand-alone riffing of Adams, Kowalski, and Newman.

I'm not a Holmes scholar, nor could I say I'm a die-hard fan, but I've always been interested, and I wanted to take the opportunity to look at the world's most famous detective in earnest. However, there are already many sites dedicated to the canonical Sherlock Holmes, and to avoid needless duplication, I'm dealing with pastiches instead of canon.

As a steampunk scholar, I've had many people ask "Is Guy Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes steampunk?" According to my aesthetic definition, there are certainly steampunk elements. The costuming and Holmes' fighting style are neo-Victorian, trading historical accuracy for stylistic verisimilitude. The uber-weapon in the film's climax has some level of retrofuturism and technofantasy, albeit light doses when compared to most steampunk tech. It's certainly no clockwork steam-spider. But that is the extent of my analysis of Ritchie's Holmes as steampunk, at least until I see the new film.

With that question so quickly answered, I am then asked if I think Downey's Holmes and Law's Watson are any good; people assume that because I deal in steampunk, I must know every work of popular Victorian and Edwardian literature intimately (I don't, but I'm working on it!). Subjectively, I think they're a brilliant spin on the odd couple Holmes and Watson have represented in their many iterations. Objectively, it's glaringly obvious that the letter of Doyle's canon has been abandoned for something closer to spirit. That said, this is nothing new in the history of Holmes onscreen. Just compare Nigel Bruce's "buffoonish portrait" of Watson in the Petrie Wine radio series, specifically "The Night Before Christmas episode" with David Burke's splendid performance in the UK Granada TV series Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which "finally [does] justice to the 'old campaigner' as a man of courage, intelligence, and compassion" (Klinger lvii). Or compare Peter Cushing's performance in "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle," one of the few surviving episodes of the '60s BBC series with Jeremy Brett in the UK Granada version of the same episode. As Klinger notes, "while Brett is not the Holmes of everyone's imagination, his larger-than-life characterisation will certainly stand for a generation as the screen Sherlock Holmes" (lvii). One might say the same for Downey and Law. But this is not the object of my inquiry either.

In preparing this post, I listened to the radio episode "The Night Before Christmas," read "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle," and watched the Cushing and Brett versions of "Carbuncle" on YouTube, these Holmes' tales (the former pastiche, the latter canon) for their seasonal relevance, which resulted in reengaging my ruminations on the absence of Christmas and Christendom in steampunk.

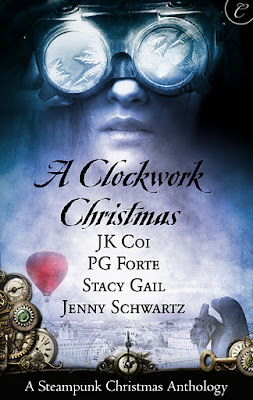

Two years ago, I pondered the absence of Christmas, and by extension Christianity, in the majority of steampunk literature. At the time, J. Daniel Sawyer's "Cold Duty" was the only steampunk story I'd read that referenced that most Dickensian of holidays. Surprisingly, of the over one hundred steampunk books on my shelf, less than half include Christendom as a facet of their steampunk world building. Of those that do, Jay Lake's Mainspring and sequels figure most notably, since Lake's alternate world takes the nineteenth century conceit of God as the cosmic clockmaker quite literally. I recently came across "Christmas Past" in Jonathan Green's Human Nature, where Christmas is simply backdrop. This year saw Lev AC Rosen's All Men of Genius, which appropriately includes a scene of festive cheer in addition to its references to Twelfth Night, as well as the release of A Clockwork Christmas, an anthology dedicated to steampunk holiday tales. Despite these few steampunk settings augmented with Yuletide cheer, references to Christendom and Christmas are less common in steampunk than one might imagine.

This dearth of reference to religion in London is odd, given the "revival of religious activity, largely unmatched since the days of the Puritans" that swept England in the nineteenth century:

One might argue more strenuously for references to Christmas in steampunk, since "what we think of as Christmas was actually invented, for the most part, in the Victorian era."

Steampunk set in an alternate world closely resembling earth needs to deal with the problem of the Church, especially when set in England. Let me be clear: I'm not advocating for a steampunked Pilgrim's Progress or nineteenth century Narnias. Painting the church in a positive light is not the issue at hand: I'm a fan of Philip Pullman's Golden Compass, which goes beyond the church as villain to God as Evil Overlord. I'm simply nonplussed at the common erasure of Church from steampunk: get rid of the Church if you like, but then deal with the ramifications of that absence. Or keep it, and let it be a power that holds back progress, giving reasons for steam technology in the 1960s, as in Keith Roberts' brilliant alternate history Pavane. That said, don't limit yourself to the stereotype of Church as the Big Bad; while certainly involved in numerous historical atrocities, Christendom was responsible for a lot more than the Crusades and Inquisition. If you're going to steampunk the emancipation of slavery, you'll be playing both sides of that coin. Or, you can simply ensure it's sitting in the background, as Kady Cross has in The Girl in the Steel Corset, citing romance fans' eye for historical detail. Obviously, there's no need for references to real-world religion in the fully secondary steampunk worlds, such as the world of Stephen Hunt's Court of the Air and its sequels. Yet even Karin Lowachee's secondary world in Gaslight Dogs has an all too familiar religion bent on colonial proselytizing that creates a instant familiarity with her ostensibly unfamiliar world.

Whatever you do, do your homework, and know your history. Whatever one's attitudes toward institutional religion, it was a major facet of Victorian life. Even if it's only present in blasphemy, as in the dialogue of Cherie Priest's heroes and heroines, ensure you haven't thrown the baby out with the bathwater, or manger straw, for Christ's sake.

With tonight's release of Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows and the Christmas season upon us, I decided to kill two birds with one stone, by introducing my Sherlock Holmes series while simultaneously riding one of my scholarly hobby horses, the use or absence of Christmas/Christendom in steampunk.

Doing a series of Holmes posts was inspired by the release of the new Guy Ritchie film, as well as by Titan Books' line of Holmes' pastiches, both in the Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes series, marked by an asterisk below, and in the stand-alone riffing of Adams, Kowalski, and Newman.

Sherlock Homes: the Breath of God by Guy Adams: Holmes and Crowley!*Sherlock Holmes: The Veiled Detective by David Stuart Davies: Holmes' Secret Origin!The Hound of the D'Urbervilles by Kim Newman*Sherlock Holmes: The Whitechapel Horrors by Edward B. Hanna: Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper!The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes by Leslie Klinger: Holmes for SMRT people!

*Sherlock Holmes: War of the Worlds by Manly W. Wellman and Wade Wellman: Holmes vs. Martians!

I'm not a Holmes scholar, nor could I say I'm a die-hard fan, but I've always been interested, and I wanted to take the opportunity to look at the world's most famous detective in earnest. However, there are already many sites dedicated to the canonical Sherlock Holmes, and to avoid needless duplication, I'm dealing with pastiches instead of canon.

As a steampunk scholar, I've had many people ask "Is Guy Ritchie's Sherlock Holmes steampunk?" According to my aesthetic definition, there are certainly steampunk elements. The costuming and Holmes' fighting style are neo-Victorian, trading historical accuracy for stylistic verisimilitude. The uber-weapon in the film's climax has some level of retrofuturism and technofantasy, albeit light doses when compared to most steampunk tech. It's certainly no clockwork steam-spider. But that is the extent of my analysis of Ritchie's Holmes as steampunk, at least until I see the new film.

With that question so quickly answered, I am then asked if I think Downey's Holmes and Law's Watson are any good; people assume that because I deal in steampunk, I must know every work of popular Victorian and Edwardian literature intimately (I don't, but I'm working on it!). Subjectively, I think they're a brilliant spin on the odd couple Holmes and Watson have represented in their many iterations. Objectively, it's glaringly obvious that the letter of Doyle's canon has been abandoned for something closer to spirit. That said, this is nothing new in the history of Holmes onscreen. Just compare Nigel Bruce's "buffoonish portrait" of Watson in the Petrie Wine radio series, specifically "The Night Before Christmas episode" with David Burke's splendid performance in the UK Granada TV series Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which "finally [does] justice to the 'old campaigner' as a man of courage, intelligence, and compassion" (Klinger lvii). Or compare Peter Cushing's performance in "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle," one of the few surviving episodes of the '60s BBC series with Jeremy Brett in the UK Granada version of the same episode. As Klinger notes, "while Brett is not the Holmes of everyone's imagination, his larger-than-life characterisation will certainly stand for a generation as the screen Sherlock Holmes" (lvii). One might say the same for Downey and Law. But this is not the object of my inquiry either.

In preparing this post, I listened to the radio episode "The Night Before Christmas," read "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle," and watched the Cushing and Brett versions of "Carbuncle" on YouTube, these Holmes' tales (the former pastiche, the latter canon) for their seasonal relevance, which resulted in reengaging my ruminations on the absence of Christmas and Christendom in steampunk.

Two years ago, I pondered the absence of Christmas, and by extension Christianity, in the majority of steampunk literature. At the time, J. Daniel Sawyer's "Cold Duty" was the only steampunk story I'd read that referenced that most Dickensian of holidays. Surprisingly, of the over one hundred steampunk books on my shelf, less than half include Christendom as a facet of their steampunk world building. Of those that do, Jay Lake's Mainspring and sequels figure most notably, since Lake's alternate world takes the nineteenth century conceit of God as the cosmic clockmaker quite literally. I recently came across "Christmas Past" in Jonathan Green's Human Nature, where Christmas is simply backdrop. This year saw Lev AC Rosen's All Men of Genius, which appropriately includes a scene of festive cheer in addition to its references to Twelfth Night, as well as the release of A Clockwork Christmas, an anthology dedicated to steampunk holiday tales. Despite these few steampunk settings augmented with Yuletide cheer, references to Christendom and Christmas are less common in steampunk than one might imagine.

This dearth of reference to religion in London is odd, given the "revival of religious activity, largely unmatched since the days of the Puritans" that swept England in the nineteenth century:

This religious revival shaped that code of moral behaviour, or rather than infusion of all behaviour with moralism, which became known as "Victoranism." Above all, religion occupied a place in the public consciousness, a centrality in the intellectual life of the age, that it had not had a century before and did not retain in the twentieth century. (Klinger xx, emphasis added)Klinger argues that it is this religious revival that provides nineteenth century society with the propriety we see so many steampunk characters engaging in: the unflappable manners of Alexia Tarabotti in The Parasol Protectorate are arguably the result of a society built on this revival of religious activity. Thankfully, Gail Carriger's books feature religious establishments to support Alexia keeping up appearances, from American Puritans in Soulless (140) to the scheming Templars of Blameless.

One might argue more strenuously for references to Christmas in steampunk, since "what we think of as Christmas was actually invented, for the most part, in the Victorian era."

Prior to the 1800s, Christmas, which had evolved from winter solstice festivals, had often been an occasion of raucous, drunken celebration. The publication of Dickens's A Christmas Carol in 1843, with its message of goodwill and charity, helped to transform the holiday into an appreciation of family and community. The words to many Christmas carols were penned in the 1800s, both in England and the United States, and the Christmas Tree was popularised by Prince Albert, who brought the practice over from his native Germany in the 1840s. (Klinger 198)Klinger wrote this footnote for "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle" in his New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, and in returning to Holmes I hope to clarify what I mean by inclusion of Christendom, Christianity, or Christmas in steampunk. Aside from Holmes' reference to Christmas as "the season of forgiveness," there is nothing particularly sentimental about "Blue Carbuncle," unless one finds "the evident warmth of the friendship between Holmes and Watson" (Klinger 197) to be so. Holmes' allusion to the religious significance of Christmas are not the words of a believer: unlike his creator, Holmes is a man of science, not spiritualism. However, as befit the times he lived in, Doyle produced a Christmas story, one which Holmes scholar and writer Christopher Morley referred to as "a Christmas story without slush" (197). If steampunk is set in the Victorian period and London locale, or seeks to evoke said period or locale, than it must needs address at the very least the religion that spawned the holiday, if not the holiday itself from time to time, either by reference to presence or absence thereof.

Steampunk set in an alternate world closely resembling earth needs to deal with the problem of the Church, especially when set in England. Let me be clear: I'm not advocating for a steampunked Pilgrim's Progress or nineteenth century Narnias. Painting the church in a positive light is not the issue at hand: I'm a fan of Philip Pullman's Golden Compass, which goes beyond the church as villain to God as Evil Overlord. I'm simply nonplussed at the common erasure of Church from steampunk: get rid of the Church if you like, but then deal with the ramifications of that absence. Or keep it, and let it be a power that holds back progress, giving reasons for steam technology in the 1960s, as in Keith Roberts' brilliant alternate history Pavane. That said, don't limit yourself to the stereotype of Church as the Big Bad; while certainly involved in numerous historical atrocities, Christendom was responsible for a lot more than the Crusades and Inquisition. If you're going to steampunk the emancipation of slavery, you'll be playing both sides of that coin. Or, you can simply ensure it's sitting in the background, as Kady Cross has in The Girl in the Steel Corset, citing romance fans' eye for historical detail. Obviously, there's no need for references to real-world religion in the fully secondary steampunk worlds, such as the world of Stephen Hunt's Court of the Air and its sequels. Yet even Karin Lowachee's secondary world in Gaslight Dogs has an all too familiar religion bent on colonial proselytizing that creates a instant familiarity with her ostensibly unfamiliar world.

Whatever you do, do your homework, and know your history. Whatever one's attitudes toward institutional religion, it was a major facet of Victorian life. Even if it's only present in blasphemy, as in the dialogue of Cherie Priest's heroes and heroines, ensure you haven't thrown the baby out with the bathwater, or manger straw, for Christ's sake.

Amen. In my (non-existent) spare time, I've occasionally wondered how hard it would be to write an alternative history story without the advent of Christianity. Suppose Mary's "fiat" was a "nyet" instead; two or three thousand years later, it seems doubtful we'd have the bland irreligious humanism supposed by Asimov and other golden age writers. I'm imagining more of a Romanesque polyglot pluralism, with overlapping levels of philosophies (from pseudo-atheistic mechanical Epicureanism to organic 'Eastern' mysticism), cults both new (technomancy) and old (Apollo and Aphrodite), and above all other allegiances, the imperial religion of Industrial capitalism and nationalism. (Assuming that we still get an Industrial revolution, for the sake of the genre.) And, of course, the continuing existence of Diaspora Judaism, the only recognizably "modern" religion from our perspective as readers.

ReplyDeleteComing from left field here, but perhaps the lack of Christianity in these works is due to something as mundane as marketing...making it appealing to the broadest swathe possible? Sounds shallow, but that's what I always guessed myself.

ReplyDeleteI agree with the need of the literature to retain something of the Church and other religions in one form or another (since they had such a deep presence in the actual 19th century) *or* a careful secularism, which as a reader, I do find a treat, if not historically accurate :)

And PS-love the blog! kudos from another academic and steampunk fan!

You might be right, L, but I'd say it comes as much from lazy assumptions about history (this has happened to First Nations people entirely in one alternate history in particular) and personal bias (you can get rid of whatever you don't like - a world without religion!). Thanks for the kudos!

ReplyDeleteCould your thoughts on the absence of Christianity extend to speculative literature as a whole? Medieval fantasy comes to mind?

ReplyDeleteIn response to Klinger, I wish one heard more 19th c. carols, and less Nat King Cole, Bing Crosby et al., catering to the tastes of nostalgia-sodden babyboomers!

D.A., I'm assuming those or two separate thoughts, or I'm hunting down the medieval fantasy inspired by Bing Crosby.

ReplyDeleteYes, I think medieval fantasy is a prime candidate for the same discussion. After so many years of fantasy gaming, where the hell is my cleric/paladin quest? Oh - I'm writing it, that's right.

Have you heard Annie Lennox's Christmas album? It's got more old-world feel. As does anything by Loreena McKennitt.

The relationship between speculative fiction and religion is always an interesting one--and I hope (and perhaps should pray to Saint Cuthbert of the Cudgel) that someday you write the definitive book on the subject; or failing that supervise the PhD dissertation on it.

ReplyDeleteOh, and I managed to dig up something I read awhile aback on 'implicit Christianity in Dungeons of Dragons' that might interest you: http://grognardia.blogspot.com/2008/12/implicit-christianity-of-early-gaming.html

I will look out for Annie Lennox. I find personally that Maddy Prior and the Carnival Band offer the best for decent old-fashioned carols. And on that note, may you and your family have a very Happy Christmas!

@michael

ReplyDeleteMichael Moorcock's Gloriana is set in a world without Christianity, and Kirk Mitchell's Germanicus trilogy is set in a world where Christianity never took off.