20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne: Part II, Chapters 8-14

Despite a stack of review books begging to be read, lesson plans laying unfinished, and a secret project deadline that looms large, I'm doggedly committed to keeping this month about Verne...(NOTE TO SELF - next year, September is going to be a month off...)

The first big reveal of 20KL is that the monster is no creature at all, but a man-made submarine far beyond the technological limitations of Verne's day. Yet this revelation is not entire, as Aronnax and his companions are quickly ushered into a dark cell within the ship. Verne maintains mastery of unveiling his mysteries. I can imagine that schoolyard conversations amongst his first readers amounted to the same type I engaged with friends in, speculating on whether Darth Vader really was Luke Skywalker's father, or modern forums devoted to television series like Lost are filled with conjectures about "what's really going on." What manner of ship have they found themselves on?

The illustrations on both of these slides are by Pablo Marcos studios, from an Illustrated Classic Editions version of 20KL I picked up from a used bookstore. While it isn't an exact replica, they are the same illustrations that filled the pages of the first edition of the book I ever owned. The cover of my current copy is different from the one I owned as a child, but I was pleased to note that Aronnax isn't rendered as an old man, and surprised at how much of the text this children's adaptation by Malvina G. Vogel covers. I utilize these illustrations in my lectures to bring attention to how Verne is primarily perceived as a "boy's adventure" writer in North America, again owing to the poor translations of 20KL. I have even had students tell me their parents are concerned they aren't studying "real literature" when they reveal the textbooks their English professor has assigned them.

Verne's next reveal introduces the character of Captain Nemo, who will remain enigmatic beyond the close of the book. Even once Verne has revealed the nature of the submarine vessel, the origin and mission of its captain will stay hidden. Brüno's spare black and white illustration is a masterful visual of how Nemo remains metaphorically in shadow. While Nemo promises to reveal the depths of the ocean floor to Aronnax, there is much he keeps hidden beneath his own surface.

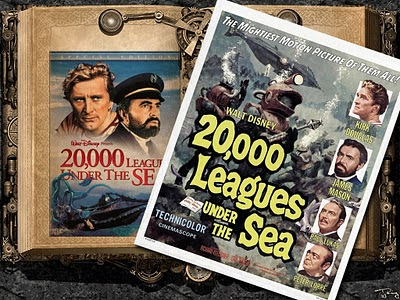

While I consider Disney's version of 20KL a classic, this is one of my biggest beefs with their storytelling decisions. Echoing James Maertens's complaints in "Between Jules Verne and Walt Disney: Brains, Brawn, and Masculine Desire in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea," the idea that Aronnax and his companions can so nonchalantly walk on board The Nautilus while Nemo and what seems to be his entire crew are busy conducting a funeral strikes me as ridiculous. Nemo is caught with his pants down, or in this case, his hatches open. Maertens's argument centers on how Disney repeatedly undermines Nemo's brilliance by presenting Ned Land as an antagonist, and turning the narrative into The Great Escape Under the Sea. It's a wonderful piece of scholarship on 20KL.

Verne's reveal of the Nautilus demonstrates his mastery of delivering didactic detail without sacrificing narrative content. Even as Verne catalogues the Nautilus's seafood delights, and the masterful use of the ocean's resources to produce clothing, perfume, pens, ink, and even cigars (I was most pleased to find that Captain Nemo shares my love for a good cigar, and am eagerly awaiting some enterprising steampunk tobacco aficionado's line of seaweed cigars), he reveals the extent of Nemo's separation from the surface world.

The library serves to underscore this even further, while engaging in one of Verne's many lists to establish verisimilitude. Even while the reader would be coming to terms with this fantastic underwater vehicle, Verne inserts reminders that this takes place in a 'real' world, not one of pure fantasy. Among Nemo's 12,000 volumes under the sea, Verne lists "Homer and Victor Hugo" among "masterpieces both ancient and modern" (72). One of Miller and Walter's footnotes relate how "Madame Sand" was a colleague of Verne's, a French romantic novelist who encouraged Verne to "take us into the depths of the sea, making your characters travel in diving equipment perfected by your science and your imagination," causing French scholars to conclude she likely inspired 20KL.

Likewise, the "thirty pictures by the masters" are listed so an exploration via Google Image could help a modern reader to imagine the sorts of images Nemo has chosen to adorn the walls of his salon. I've not had time to investigate these artworks in depth, and so have not speculated whether they were chosen by Verne as a character reveal, or simply as representative of Verne's own artistic tastes. This is definitely one of the moments that undermines Verne's later choice for Nemo's heritage, since the art is all European. It is more likely a demonstration of the original intention for Nemo's background as a Polish aristocrat seeking revenge against Russia, a decision censored by Verne's publisher, Pierre Hetzel. Nevertheless, between the listing of books and art, a young French reader may have been inspired to reading or viewing of classics, depending on their proximity and accessibility to a museum or library. I can't help but again make a comparison to Arthur Slade's Hunchback Assignments, which maintain this intertextual cataloging through a protagonist who loves literature.

From food to art to literature and onto the technical details of navigation, Verne reveals the wonders of the Nautilus, all the while teaching his readers, so that a number of children's books about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea contain diagrams and photographs further illuminating the facts Verne can only briefly touch upon. The images of the Compass and Barometer featured in the following slide are scanned from Deluxe Classics 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which features both an adaptation of the story as well as numerous side-bard illustrations and captions. Another fantastic edition sharing this approach is Oceanology: The True Account of the Voyage of the Nautilus, with its gorgeous "Ologies" elements of envelopes containing letters, holographic images, intricate charts, and antique-style maps.

Both books contain cut-away schematic diagrams of the Nautilus, joining a long list of artists' renditions of Nemo's amazing vessel. As I have mentioned elsewhere, Harper Goff's design of the Nautilus for the 1954 Disney film version of 20KL might well be one of the greatest inspirations for the steampunk aesthetic. It also stands as one of the greatest inspirations for artists looking to submit their own spin on the Nautilus' design. Take a look through the wonderful list of Nautilus designs at the Catalog of Nautilus designs, which limits its content to ships that don't depart drastically from Verne's vision (as in the case of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). You can see in the following slide how the designs have progressed from the cigar-like cylinder of the book to a mix of highly functional, or exceedingly stylized versions.

Finally, unless the truly devoted reader of Verne's texts takes the time to peruse the image database at Zvi Har'El's excellent website of all-things-Verne, they'd miss the opportunity original readers had in puzzling out those "info-dumps" of sea-life classification. Take a look at the first slide, which shows the image the Naval Institute edition includes, and then check out the second slide of a labeled drawing, which would have enabled readers to match up the sea-life with the text's descriptions. For Verne's first readers, these illustrations were a window into an underwater world beyond their means of exploration. In a post-Cousteau world, we may be too jaded to appreciate the value of these drawings. My recommendation to modern readers is to take those labeled versions, and once again play with Google Image. The second slide has a collage of my own image search. We have the opportunity to take a similar journey in ways even Verne didn't dream of. Let's not take that for granted. Think of it as homework for next 'lecture'!

The first big reveal of 20KL is that the monster is no creature at all, but a man-made submarine far beyond the technological limitations of Verne's day. Yet this revelation is not entire, as Aronnax and his companions are quickly ushered into a dark cell within the ship. Verne maintains mastery of unveiling his mysteries. I can imagine that schoolyard conversations amongst his first readers amounted to the same type I engaged with friends in, speculating on whether Darth Vader really was Luke Skywalker's father, or modern forums devoted to television series like Lost are filled with conjectures about "what's really going on." What manner of ship have they found themselves on?

The illustrations on both of these slides are by Pablo Marcos studios, from an Illustrated Classic Editions version of 20KL I picked up from a used bookstore. While it isn't an exact replica, they are the same illustrations that filled the pages of the first edition of the book I ever owned. The cover of my current copy is different from the one I owned as a child, but I was pleased to note that Aronnax isn't rendered as an old man, and surprised at how much of the text this children's adaptation by Malvina G. Vogel covers. I utilize these illustrations in my lectures to bring attention to how Verne is primarily perceived as a "boy's adventure" writer in North America, again owing to the poor translations of 20KL. I have even had students tell me their parents are concerned they aren't studying "real literature" when they reveal the textbooks their English professor has assigned them.

Verne's next reveal introduces the character of Captain Nemo, who will remain enigmatic beyond the close of the book. Even once Verne has revealed the nature of the submarine vessel, the origin and mission of its captain will stay hidden. Brüno's spare black and white illustration is a masterful visual of how Nemo remains metaphorically in shadow. While Nemo promises to reveal the depths of the ocean floor to Aronnax, there is much he keeps hidden beneath his own surface.

While I consider Disney's version of 20KL a classic, this is one of my biggest beefs with their storytelling decisions. Echoing James Maertens's complaints in "Between Jules Verne and Walt Disney: Brains, Brawn, and Masculine Desire in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea," the idea that Aronnax and his companions can so nonchalantly walk on board The Nautilus while Nemo and what seems to be his entire crew are busy conducting a funeral strikes me as ridiculous. Nemo is caught with his pants down, or in this case, his hatches open. Maertens's argument centers on how Disney repeatedly undermines Nemo's brilliance by presenting Ned Land as an antagonist, and turning the narrative into The Great Escape Under the Sea. It's a wonderful piece of scholarship on 20KL.

Verne's reveal of the Nautilus demonstrates his mastery of delivering didactic detail without sacrificing narrative content. Even as Verne catalogues the Nautilus's seafood delights, and the masterful use of the ocean's resources to produce clothing, perfume, pens, ink, and even cigars (I was most pleased to find that Captain Nemo shares my love for a good cigar, and am eagerly awaiting some enterprising steampunk tobacco aficionado's line of seaweed cigars), he reveals the extent of Nemo's separation from the surface world.

The library serves to underscore this even further, while engaging in one of Verne's many lists to establish verisimilitude. Even while the reader would be coming to terms with this fantastic underwater vehicle, Verne inserts reminders that this takes place in a 'real' world, not one of pure fantasy. Among Nemo's 12,000 volumes under the sea, Verne lists "Homer and Victor Hugo" among "masterpieces both ancient and modern" (72). One of Miller and Walter's footnotes relate how "Madame Sand" was a colleague of Verne's, a French romantic novelist who encouraged Verne to "take us into the depths of the sea, making your characters travel in diving equipment perfected by your science and your imagination," causing French scholars to conclude she likely inspired 20KL.

Likewise, the "thirty pictures by the masters" are listed so an exploration via Google Image could help a modern reader to imagine the sorts of images Nemo has chosen to adorn the walls of his salon. I've not had time to investigate these artworks in depth, and so have not speculated whether they were chosen by Verne as a character reveal, or simply as representative of Verne's own artistic tastes. This is definitely one of the moments that undermines Verne's later choice for Nemo's heritage, since the art is all European. It is more likely a demonstration of the original intention for Nemo's background as a Polish aristocrat seeking revenge against Russia, a decision censored by Verne's publisher, Pierre Hetzel. Nevertheless, between the listing of books and art, a young French reader may have been inspired to reading or viewing of classics, depending on their proximity and accessibility to a museum or library. I can't help but again make a comparison to Arthur Slade's Hunchback Assignments, which maintain this intertextual cataloging through a protagonist who loves literature.

From food to art to literature and onto the technical details of navigation, Verne reveals the wonders of the Nautilus, all the while teaching his readers, so that a number of children's books about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea contain diagrams and photographs further illuminating the facts Verne can only briefly touch upon. The images of the Compass and Barometer featured in the following slide are scanned from Deluxe Classics 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which features both an adaptation of the story as well as numerous side-bard illustrations and captions. Another fantastic edition sharing this approach is Oceanology: The True Account of the Voyage of the Nautilus, with its gorgeous "Ologies" elements of envelopes containing letters, holographic images, intricate charts, and antique-style maps.

Both books contain cut-away schematic diagrams of the Nautilus, joining a long list of artists' renditions of Nemo's amazing vessel. As I have mentioned elsewhere, Harper Goff's design of the Nautilus for the 1954 Disney film version of 20KL might well be one of the greatest inspirations for the steampunk aesthetic. It also stands as one of the greatest inspirations for artists looking to submit their own spin on the Nautilus' design. Take a look through the wonderful list of Nautilus designs at the Catalog of Nautilus designs, which limits its content to ships that don't depart drastically from Verne's vision (as in the case of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). You can see in the following slide how the designs have progressed from the cigar-like cylinder of the book to a mix of highly functional, or exceedingly stylized versions.

Finally, unless the truly devoted reader of Verne's texts takes the time to peruse the image database at Zvi Har'El's excellent website of all-things-Verne, they'd miss the opportunity original readers had in puzzling out those "info-dumps" of sea-life classification. Take a look at the first slide, which shows the image the Naval Institute edition includes, and then check out the second slide of a labeled drawing, which would have enabled readers to match up the sea-life with the text's descriptions. For Verne's first readers, these illustrations were a window into an underwater world beyond their means of exploration. In a post-Cousteau world, we may be too jaded to appreciate the value of these drawings. My recommendation to modern readers is to take those labeled versions, and once again play with Google Image. The second slide has a collage of my own image search. We have the opportunity to take a similar journey in ways even Verne didn't dream of. Let's not take that for granted. Think of it as homework for next 'lecture'!

Hey K.L. Both "Perdido" and "Whitechapel Gods" are pretty gritty steampunk. Those worlds are definitely ugly and cruel, and are indicative of one end of the steampunk aesthetic. You're looking for something more fun and optimistic. I'd recommend any of the following: Kenneth Oppel's Airborn series, The Parasol Protectorate Series by Gail Carriger (starts with Soulless), The Adventures of Langdon St. Ives by James Blaylock, The Hunchback Assignments by Arthur Slade, The Leviathan series by Scott Westerfeld, The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers.

ReplyDeleteOh, and thanks very much for the very kind words, K.L. I'm glad to hear my recommendation to read 20KL (I was mistaken in making it 2KL initially - that would only be 2,000 Leagues Under the Sea!) has merited a favorable response. Let me know how those recommendations pan out for you.

ReplyDelete